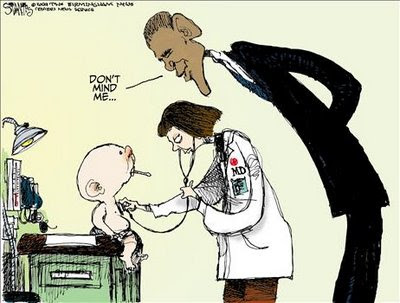

Pundit Newswire: The ERISA Pundit testified on August 28, 2012 before the Department of Labor’s ERISA Advisory Council. Although the Pundit’s oral testimony is not publicly available, the Department of Labor has released the Pundit’s written statement here. The mood in Washington is exemplified by this cartoon, and the Pundit’s written statement is excerpted below:

Written Statement to the Dept of Labor ERISA Advisory Council

by

The ERISA Pundit (sub nomine Warren von Schleicher)

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act represents a balancing of diverse interests. The desire to provide comprehensive welfare benefit plans to employees, including a system for fair and prompt enforcement of rights, must be balanced with the need to encourage employers to provide these voluntary benefit plans. Encouraging employers to provide long-term disability benefit plans is particularly important at this time.

Employers have limited budgets for welfare benefit programs, and a significant portion of those budgets must be allocated to mandatory health care coverage. In the current economy, employers may not need to provide disability plans in order to attract and retain good workers.

Only 30% of employers provide long-term disability plans to their employees. Unfortunately that number may erode as employers incur increased financial responsibility for employee health care. Disability programs must vie with many other important welfare benefit programs, including life, dental, senior care, and eye care, for any remaining portion of the employer’s limited budget.

In addition to the impediment of limited employer budgets, disability benefit plans face the impediment of inaccurate disability risk perception among employees in general. Employees, in prioritizing the type of benefit programs they desire for their families, may assign lower priority to long-term disability coverage, which insures an impalpable risk that statistically may not occur, and higher priority to (for example) dental coverage, which provides tangible financial returns for all employees and their families every year. Approximately 12% of American workers will become “disabled” for five or more years during their careers, according to criteria and data reported by the Social Security Administration. But most American workers believe they have only a 2% or less chance of becoming disabled during their careers. The actual risk of disability, therefore, is significantly higher than employees’ perceived risk of disability.

Most employers who desire to provide disability benefit plans to their employees, and are financially able to do so, lack the infrastructure and expertise to self-fund and administer their plans. For most employers, therefore, insurer funded and administered disability benefit plans are the only viable option.

Disability insurers spend significant time and resources educating employers and employees about the risk of disability occurrence and the financial impact of disability on employees and their families. Disability insurers also provide significant flexibility in disability program design, in order to provide affordable coverage options for employers and their employees. And some insurers take the additional step of providing claims representatives on-site at the employer’s workplace to facilitate education, enrollment, and the filing of disability claims.

The paramount social concern is for the Department of Labor to permit incentives to exist that encourage employers to offer voluntary disability plans to their employees. Overregulation risks higher administrative costs and employer retraction, which reduces the number of employees who have coverage, and places greater strain on state and federal social programs. Employers are not required to provide disability coverage as an incentive to retain workers, particularly in the current employment environment. Insurers must be able to provide cost effective coverage to encourage employers to provide these programs, under a flexible set of regulations that provide for a full and fair review of claims without complexities that unduly discourage plan formation.

Full and Fair Review

The core requirements of a “full and fair” review include knowing the reasons for the administrator’s benefit decision, having an opportunity to appeal, and obtaining a timely final decision that considers the relevant evidence. See 29 U.S.C. §1133. Providing adequate notice of an initial adverse decision permits participants to address any issues in the evidence and to provide additional information in support of their disability claims. The administrative appeal provides a “reasonable opportunity … for a full and fair review by the appropriate named fiduciary of the decision denying the claim.” 29 U.S.C. §1133(2).

In addition, ERISA’s disability regulations establish procedures for the review of adverse claim determinations, including:

Provid[ing] for a review that takes into account all comments, documents, records, and other information submitted by the claimant relating to the claim, without regard to whether such information was submitted or considered in the initial benefit determination; and

Provid[ing] that, in deciding an appeal of any adverse benefit determination that is based in whole or in part on a medical judgment, … the appropriate named fiduciary shall consult with a health care professional who has appropriate training and experience in the field of medicine involved in the medical judgment.

29 C.F.R. §2560.503-1(h)(2)(iv); 29 C.F.R. §2560.503-1(h)(3)(iii).

Under ERISA’s current regulatory framework, the vast majority of disability claims are approved during the administrative review process. While statistics may vary, generally more than 80%-85% of disability claims are approved and resolved administratively. By contrast, only 35% of Social Security disability claims are initially approved. (See Social Security Admin., 2011 Disabled Worker Beneficiary Statistics, at www.ssa.gov). Only a fraction of unapproved ERISA disability claims result in litigation, and in many instances the administrator’s decision is judicially upheld.

Plaintiffs’ lawyers may highlight their personal litigation losses and deem ERISA a broken, unfair system, and ardently advocate ways to tilt the balance to favor more litigation victories and more awards of attorneys’ fees. They call for jury trials, which is incompatible with ERISA’s foundation in trust law. They call for punitive damage awards, which is inconsistent with the remedies provided by Congress in 29 U.S.C. §1132(a), increases the cost of incorrect decisions at the expense of the vast majority of correct decisions, and discourages employers from voluntarily offering disability benefit plans. And they call for a national ban on discretionary clauses, which impedes national uniformity as the Supreme Court recently addressed in the context of pension plans in Conkright v. Frommert, – U.S. -, 130 S.Ct. 1640 (2010) (warning of the potentially disastrous consequences if discretionary clauses were not judicially enforced, leading to a patchwork system of inconsistent judicial results that vary from state to state).

One cannot evaluate ERISA’s regulatory efficacy by myopically focusing on claims in litigation, which is the smallest percentage of disability claims. Claims in litigation are not representative of the much broader universe of disability claims, the vast majority of which are approved through adherence to ERISA’s current statutory and regulatory requirements for a full and fair review.

Administrators strive to provide participants with a full and fair review of the evidence and reach decisions that are fully informed, impartial, well-reasoned, and correct. Viewed from the perspective of all disability claims, most of which are approved, very few claims will lead to a judicial finding that the participant was deprived of a full and fair review. For employers and insurers charged with designing and implementing disability plans under ERISA’s regulatory framework, the statistics demonstrate that ERISA’s goal of providing a financial safety net for millions of disabled American workers largely has been achieved.

The objective of the Department of Labor at this time should not be to tilt the balance to favor plaintiffs and their attorneys in litigation. Rather, the goal should be to create incentives that encourage the remaining 70% of employers who do not offer disability benefit plans to do so, under a system that facilitates the cost-effect creation of insurer-funded disability plans and administrative flexibility.

Providing participants with a full and fair review of their disability claims is not without challenges. In litigation, plaintiffs have argued that during an administrative appeal, they should receive pre-decision access to documents generated during the appeal and an opportunity to provide rebuttal. But that circular procedure would create an endless cycle. The participant’s rebuttal would require review, which would generate additional pre-decision documents, and require another opportunity for rebuttal.

Disability determinations are complex and multidisciplinary, often requiring vocational evaluation, financial analysis, and medical consultation. The medical component alone frequently encompasses numerous medical specialties. It is difficult enough to decide disability appeals within the curtailed 45-day time regulatory period (even with one 45-day extension). Adding additional layers of rebuttals within appeals would thwart the ability to make timely final decisions and ultimately risk affecting the quality and accuracy of final decisions.

Rejecting such a never-ending cycle of rebuttals, the Tenth Circuit stated: “Permitting a claimant to receive and rebut medical opinion reports generated in the course of an administrative appeal—even when those reports contain no new factual information and deny benefits on the same basis as the initial decision—would set up an unnecessary cycle of submission, review, re-submission, and re-review. This would undoubtedly prolong the appeal process, which, under the regulations, should normally be completed within 45 days. Moreover, such repeating cycles of review within a single appeal would unnecessarily increase cost of appeals.” Metzger v. Unum Life Ins. Co. of Am., 476 F.3d 1161, 1166-1167 (10th Cir. 2007) (internal citations omitted).

ERISA disability decisions are already complex, come in many permutations, and require multidisciplinary analysis. Adding an additional rebuttal round onto the review procedures would add further complexity to the already short 45-day review period, without any indicia whatsoever that the outcome would be more accurate, timely claim decisions.

Currently, disability claims administrators generally apply a flexible approach when reviewing claims on appeal. In fact specific circumstances, a physician or other expert consultant may contact the participant’s treating physician to discuss medical issues and obtain additional information, or the administrator may contact the participant or her attorney to discuss evidence obtained during the appeal. In other fact specific circumstances, the record contains sufficient information to reach an informed and independent benefit eligibility decision. This flexibility allows the review process to adapt to the unique circumstances of each claim, and best serves ERISA’s goals, including the interest of participants in obtaining a timely final decision.

Financial Integration with Social Security Disability Income

The ERISA Advisory Council has received written testimony on the integration of Social Security disability income (“SSDI”) with ERISA-governed disability plans, including testimony from the American Council of Life Insurers. The financial integration of SSDI with disability plans, in the form of offsets, reflects a careful balance between providing a sufficient level of disability benefits and preventing the creation of perverse financial inducements that reduce the incentives to return to work.

Many, but not all, disability benefit plans provide that monthly disability benefits are to be reduced by the base amount of Social Security disability benefits a participant receives. Typically SSDI offsets do not include annual SSDI cost of living increases. The inclusion of SSDI offsets is an issue of employer choice, which is fundamentally driven by budgetary constraints. Without integrating SSDI offsets, premiums for insurer-funded disability benefit plans would increase approximately 30% to 50% (by some estimates even more). As a result of the integration of SSDI, disability benefit plans become an affordable option for employers who desire to provide these plans to their employees.

It is important to stress that the integration of SSDI with ERISA disability benefits plans is financial in nature. An award of SSDI does not mean that the participant qualifies for disability plan benefits, and for good reason. Employers will not provide voluntary benefit plans if their plans are coopted by the government and they must bow to the disability determinations of the Social Security Administration. Moreover, there are critical differences between Social Security and disability benefit plans. Social Security determinations are made according to a grid system in a multi-step process utilizing presumptions and other short-cuts, including presumptions about certain medical symptoms and age, as part of a governmental bureaucracy. SSDI determinations may take many months or even years.

Disability benefit plans are voluntary employer-sponsored programs. They reflect a congressional balancing of diverse interests. Disability plans are tailored to address specific employer and employee needs and limitations, and do not utilize the presumptions and short-cuts that are necessary to keep Social Security functioning.

Disability benefit plans provide a higher level of income replacement than Social Security is able to provide. The average monthly SSDI benefit is $1,065, which is below the poverty threshold. Disability benefit plans ensure that participants receive approximately 60%-65% of their prior earnings (which actually replaces a larger percentage of earnings when tax advantages are factored).

Disability benefit plans ensure that disabled workers receive monthly payments shortly after they cease working, often months or even years before Social Security disability benefits are paid. Disability benefit plans, therefore, provide a sustainable safety net for millions of American workers and their families who would be unable to survive on Social Security alone.

Return to Work Incentives

The Council admirably seeks to examine the management of disability risks “in an environment of individual responsibility.” But individual responsibility is sometimes missing in the context of disability benefit plans. Benefit plans provide monthly disability benefit payments. Plans also provide an array of important non-monetary benefits that participants too frequently discount and disregard. These non-monetary benefits include coverage for reasonable accommodation expenses, retraining programs, vocational counseling, and job placement services, all aimed at facilitating the return into the work force. Even if these important return to work services were mandatory, their success depends on the participant’s desire and motivation to return to work.

Benefits paid over time have the unfortunate consequence of eroding motivation, and sometimes creating a sense of entitlement. Individual responsibility means assuming direct responsibility for one’s future, including taking steps to secure a better future. While some participants’ medical conditions prevent them from pursuing the variety of return to work programs offered by disability benefit plans, many more participants could benefit from these programs but decline to do so. The Department of Labor should partner with employers to find effective means to promote the variety of return to work programs offered by disability benefit plans.